Community Health Impact Assessments

Introduction

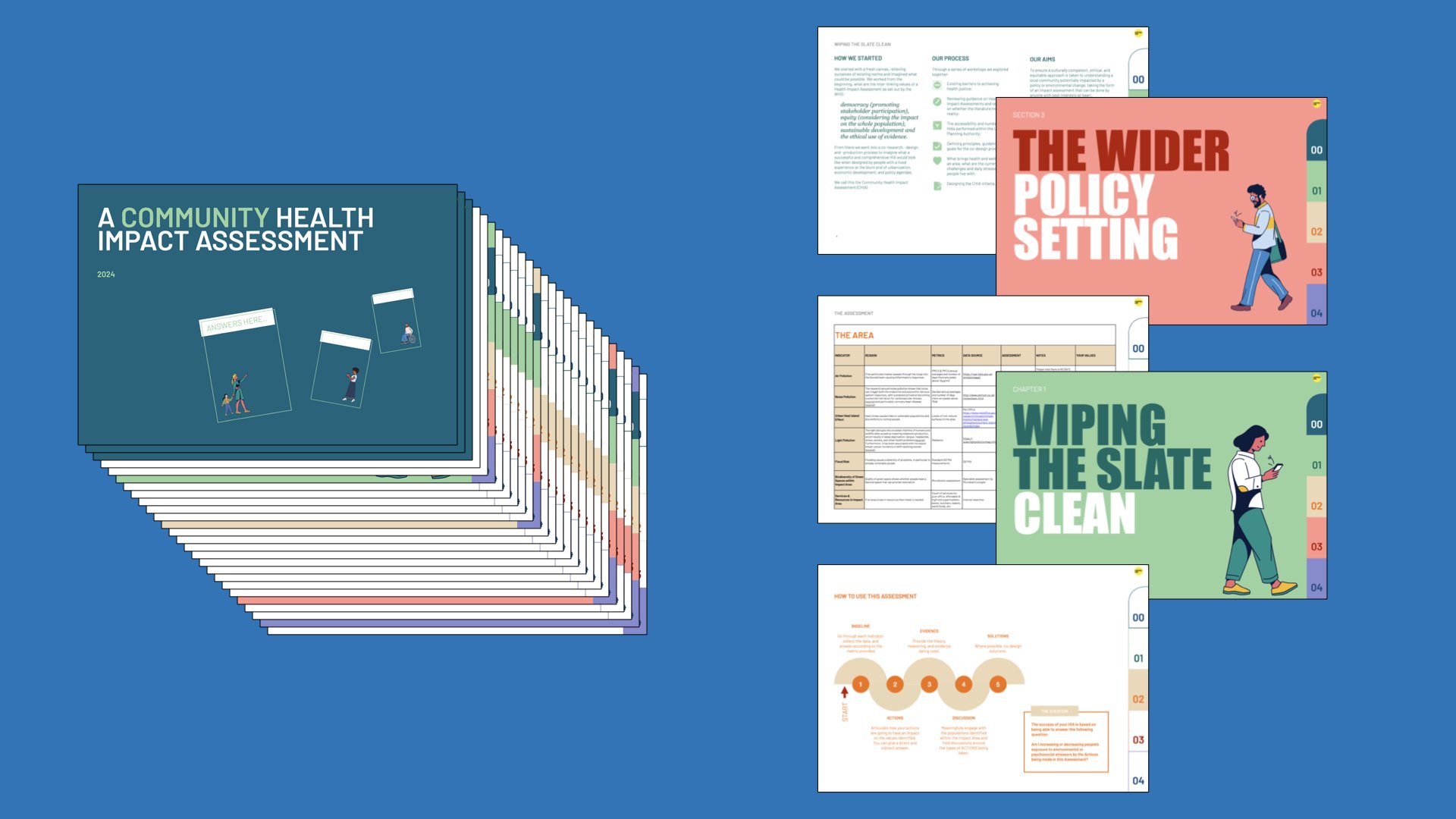

Welcome to the Community Health Impact Assessment programme page.

This programme has been co-developed with grassroots organisations in the UK.

This work aims to throw away the rule book on the status quo and imagine what an HIA could look like if it embodied the WHO four interlinking pillars of democracy, equity, ethical use of evidence, and sustainable development from a community and lived experience framing.

These exercise books, templates, learnings, and reportings are designed to help you imagine what you can do and why this area of work can be meaningful to change in the way things are done.

This Community Informed Health Impact Assessment has been designed, reviewed, and consented by C.A.S.H. for use by others like us. It is intended to ensure that all considerations towards people’s health is taken when reviewing potential impacts as a result of construction or a new urban development. It has been designed in good faith to allow for effective, intentional, and important dialogues happen between communities like ours and those looking to make changes in our neighbourhoods.

This justice-led toolkit is designed to support grassroots community groups co-producing a community informed Health Impact Assessment (HIA).

This toolkit is designed to be used by grassroots organisations without the interference of domineering authorities. This is to give space and time for people to imagine a way something could be done, rather than being shoehorned into what’s permitted

This piece documents the process that was taken in how we created our Community Health Impact Assessment. We've done this to show what journey we took in the aims of transparency and hopefully inspiration to others.

Is there a history of people and communities who have been working in this space? Are there any insights we can learn and be inspired by?

This piece helps summarise the official guidance on Health Impact Assessments. From the World Health Organisation's writings down to UK Local Planning Authorities this piece helps give a policy grounding into the topic

This is a peer-to-peer co-learning programme for urban(isation) focused community groups to develop community-led Health Impact Assessments. This is a programme for people and organisations who want to address the ecological systemic factors that influence our health at the local policy level, and seek lasting change to the places where they live.

This programme grew from the long term collaboration between Centric Lab and Clean Air for Southall & Hayes (CASH). CASH are a grassroots organisation made up of multi-ethnic working class people from Southall, West London, who have been advocating for the rights to not be unjustly polluted and exposed to toxic chemicals.

Their ongoing campaigning demonstrates the entrenched power the Right to Pollute culture has in western worlds. A big question that has always been asked is why was such little care given? This work has aimed to encompass our years of working together, since 2018, and support grassroots organisations around the UK (and beyond) in ways to challenge the system and identify pathways for policy and practice change.

This work is dedicated to all the Angela Fonso’s out there standing up for their rights, protecting the air their kids breathe, and believing that things can be better.

More About This Project

-

A community-led HIA allows for peoples lived experiences of engaging with systems that change their neighbourhoods and livelihoods to shape what democracy, equity, ethical use of data, and sustainable development look like.

A community-led HIA gives power to citizens to shape how health, in an urban context, is experienced and discussed. This reduces siloed power and creates dialogue between stakeholders.

A community-led HIA endeavoured to be more accurate, create dialogues, be less-data determinist and reduce the concept of “scoring”.

A community-led HIA without an equitable process of good governance will only break trust between communities and the people creating change around them.

-

We feel that our learnings are not isolated. The authors of the Influencing Healthy Public Policy with Community Health Impact Assessment 2009 report by the National Collaborating Centre for Health Public Policy of Quebec, Canada wrote:

Community members who were involved in the CHIA continue to comment about the value of the process. It is clear that CHIA contributed to a respectful, participatory discussion where different points of view were heard and valued. The process helped to reduce the tension in the community, provided the Concerned Ratepayers with a forum for their concerns to be raised, and offered a reasoned, neutral report for the municipal council that outlined the potential positive and negative effects of the project.

Lastly, the HIA is not defined by any one piece of legislation or policy, it is malleable and within the powers of authorities and agencies to use to their best advantages. By creating spaces for community groups to (co)develop HIAs on different topics authorities and agencies are able to demonstrate other goals of justice, equity, diversity and inclusion (JEDI) in non-tokenistic ways - meaningfully shape policy and organisational practice.

When an authority allows a community to co-develop practices based on their lived experiences they can tackle issues systemically and undo systems of harm and malpractice.

Related Reading

This working board is for people who are not “professionals” within the legal, policy, or advocacy space (NGOs) but for community-led organisers looking to develop action plans and theory of change models. The MIRO board has a series of instructions after an introduction section that you can refer to at different times.

The purpose of the Environmental Data for Health Justice board is to build confidence in how those seeking structural health justice outcomes through research, campaigns, and other forms of advocacy use data as a language to directly address health injustices and develop strategies for health justice.

Endocrine disruptors are chemicals that are ingested from our external environment through our skin, respiratory tracks, and mouth.

Biological inequity, also known as biological inequality, refers to “systematic, unfair, and avoidable stress-related biological differences which increase risk of disease, observed between social groups of a population”.

The purpose of this data led study is to bring attention to everyday people those who have the right to pollute in their neighbourhoods, so that people can make more informed decisions when it comes to voting and priorities for our shared health and climate change action points.

There is now a very clear understanding that environmental hazards, such as air pollution have a direct effect on our health. However, what is often missing from the conversation is how environmental hazards, due to being an experience of stress and trauma can lead to mental distress. In addition to the disproportionate exposure to health hazards, being aware of the injustice underlying this disproportionate exposure may be a psychosocial stressor that affects health negatively.

This data led article explores how this winter homes in areas of high pollution and deprivation with low EPC ratings are a toxic cocktail for health risks.

This article explores how “regeneration” is a word used to promote positive benefit from construction and urbanisation. It focuses on the “regeneration” of former gasworks, brownfield sites, in existing urbanised areas and the health implications with an economic led “regeneration” mantra.

At the crux of this theory is that when the body is faced with stressors it adapts through a process called allostasis, which means “achieving stability/homeostasis through change”.

We are going to use diabetes as a case study to produce three learnings. (1) Genetics are not the full story when it comes to non communicable diseases such as diabetes. (2) Understand that disease prevention and even cure is not just in the confines of medical institutions. (3) The need for geospatial studies to understand the interlink between diabetes and place.

This report lays out why there is a need to understand the history behind framing health as “individual choices” or “behaviours” to better appreciate what an ecological health approach looks like and its significance in eradicating health inequities.

The mission of this report is to reframe the culture around data to ensure that we understand its limitations, reframe from supremacy to a tool for justice, and introduce a more accurate lexicon so we can better our collective understanding of data.

Community Sovereignty is an umbrella term that brings together methods of practice for organisations and scientific researchers to establish equitable engagement with communities.

Data does not operate in a vacuum as every part of the process is coloured by top down factors such as culture. Which data is collected, how it is analysed and the insights drawn from data are all decision points practitioners have to make and all practitioners belong to a specific culture which influences them.

In this report, we look at equitable engagement with community expertise and why it is essential to move towards equitable health solutions. We will define ‘equitable engagement’; reframe the relationship between community and science; and provide a ‘How To’ manual.

This is a term identified by Centric Lab to define a knowledge pool that self-identifies as supreme to systematically dictate the knowledges that are valuable, trusted, and acknowledged, resulting in hegemonic policies that affect our health.

Our body does not only suffer chronic stress due to pollutants. Psychosocial factors also play a part in our long-term health. The psychosocial relationship to health is a widely investigated field.

This report is for those working in transport planning and in policy and who are interested in understanding the link between equitable mobility and health. This report will lay out the need for equitable solutions around transport, how health is related to mobility, and a breakdown of equitable mobility zones.

A stressor is defined as a novel threatening environmental agent that alters the baseline human biological system in either of two ways: bringing the system to an unstable biological state, or slowing down the system’s internal response so that it cannot reach equilibrium.

Environmental inequity is the systemic, avoidable, and unjust distribution of ecologically healthy environments (those that are free from pollutants, have high biodiversity, and have a healthy microbiome). It also refers to land being unjustly stolen, polluted, or damaged. In this essay, we will be detailing the pathways of oppression, including the role that science, policy, and city organisers play.

It is imperative for health organisations to provide guidelines based on the specific population under investigation: what is the susceptibility to health hazards of the individuals in the community?

This paper investigates how COVID-19 is interacting with these environments and their communities, specifically Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) communities in the UK. Specifically, this paper will look at the phenomenon of biological inequality and its relation to COVID-19 in BAME communities of London.

Centric Lab worked alongside Clean Air for Southall & Hayes to design a susceptibility study. This was in aid of demonstrating to authorities that current regulations on air pollution limits and management techniques fail those already exposed to high levels of environmental and psychosocial stressors, such as the multi-ethnic working class community of Southall, west London.

This document illustrates the systemic and biological relationship between people and their habitats. Secondly, we are seeing an increase of mental health disorders like depression, anxiety, and PTSD as well as metabolic disorders such as diabetes and obesity.

Supporting this Programme

If you are in a position of influence to help this programme develop further please get in touch with us: hello@thecentriclab.com