Naturally Occurring Green House Emissions to know

Human activity, especially at scale, has not just produced particulates that harm us. In the case of three major greenhouse gases (GHGs), large-scale human activity has also disturbed the balance of naturally occurring gases to the point that global warming takes place because the ecosystem is not able to adapt. Understanding the basic dynamics of these three GHGs, carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O), is useful for restorative campaigns and health justice.

Global 2010 GHG Emissions by Gas.

https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-data

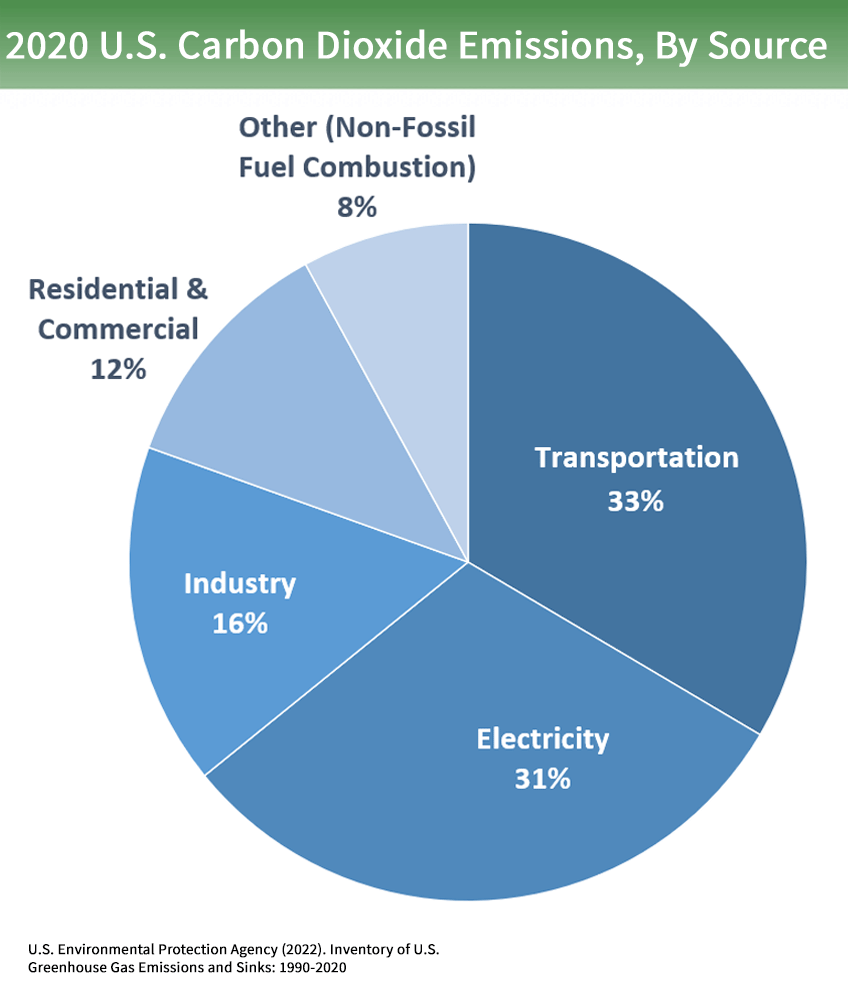

Carbon Dioxide Emissions

In 2020, CO2 accounted for 79% of the U.S. GHG emissions. CO2 is naturally present as part of the Earth's carbon cycle (the natural circulation of carbon among the atmosphere, oceans, soil, plants, microorganisms, and animals). Human activities are altering the carbon cycle by adding more CO2 to the atmosphere and by influencing the ability of natural sinks, like forests and soils, to remove and store CO2 from the atmosphere. This effect has been substantial since the industrial revolution.

The main human activities that contribute to CO2 emissions are:

The combustion of fossil fuels to transport people and goods.

The combustion of fossil fuels to generate high amounts of electricity to power homes, business, and industry.

Fossil fuel consumption, including chemical reactions, in industrial processes such as the production of mineral products, metals, and chemicals.

Because CO2 is the most prominent, it varies widely in how long it can stay in the atmosphere. Some of the excess CO2 will be absorbed quickly (for example, by the ocean surface), but some will remain in the atmosphere for thousands of years.

Greenhouse warming potential (GWP) is the main indicator of how effective a gas is at trapping heat. You will generally see a number representing the potential over a 100 year period (though the 20 year impact is popular in some uses). CO2 has a 100-year GWP of 1 because it is used as the reference point for how other gases are measured, just as it is when measuring gas concentration.

The key steps to CO2 reduction are primarily through fossil fuel reduction and include:

Energy efficiency in buildings, vehicles, and electrical appliances.

Energy conservation in personal energy usage.

Switching to renewable, less carbon-based energy sources.

Carbon capture and sequestration in new and existing coal- and gas-fired plants, industrial processes, and other stationary sources of CO2.

Changes in land usage and land management practices.

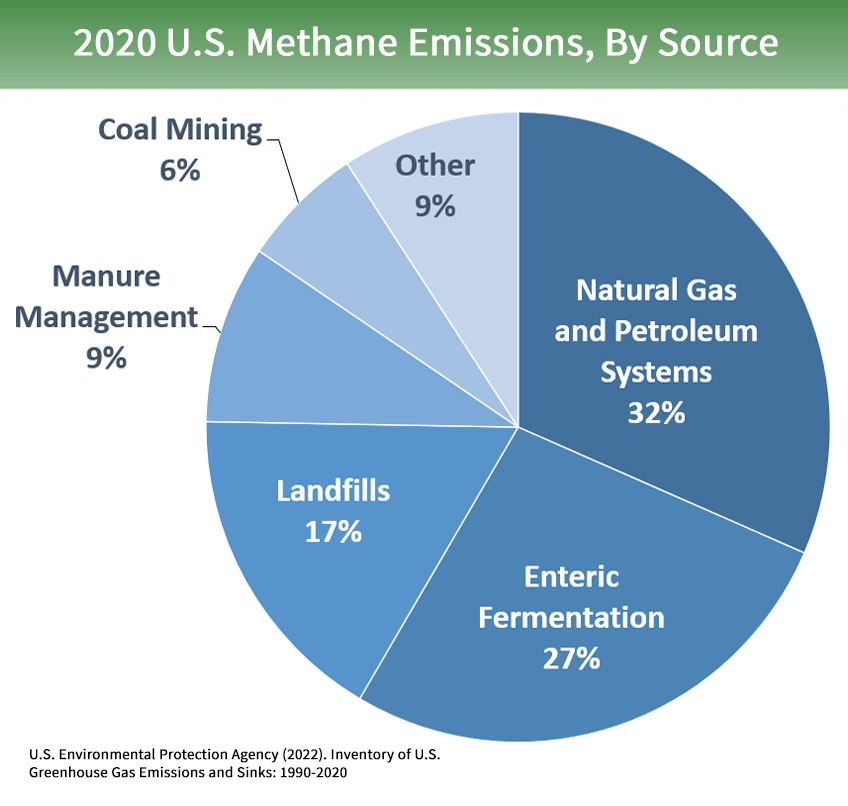

Methane Emissions

In 2020, methane (CH4) accounted for 11% of the U.S. GHG emissions. The natural cycle for CH4 is to first be emitted by sources such as natural wetlands. Natural processes in soil and chemical reactions in the atmosphere then help remove CH4 from the atmosphere.

The main human activities that contribute to CH4 emissions are:

Agriculture due to animal digestive processes and manure at scale in addition to land use.

Energy and industry due to the prominence of methane in natural gas and petroleum systems.

Waste treatment from homes and businesses.

CH4 lifetime in the atmosphere is much shorter than CO2, but CH4 is more efficient at trapping radiation than CO2. CH4 stays in the air for up to 12 years. CH4 has a GWP of 25. This means, pound for pound, the comparative impact of CH4 is 25 times greater than CO2 over a 100-year period.

A few of the most important steps to CH4 reduction include:

Altering manure management and feeding strategies for livestock.

Upgrading the equipment used to produce, store, and transport oil and natural gas as well as capturing and using methane from coal mines as energy.

Innovative reduction strategies around capturing landfill methane from wastewater.

Nitrous Oxide Emissions

In 2020, nitrous oxide (N2O) accounted for 7% of the U.S. GHG emissions. Nitrous oxide emissions occur naturally through many sources associated with the nitrogen cycle, which is the natural circulation of nitrogen among the atmosphere, plants, animals, and microorganisms that live in soil and water. Natural emissions of N2O are mainly from bacteria breaking down nitrogen in soils and the oceans. Nitrous oxide is then removed from the atmosphere when it is absorbed by certain types of bacteria or destroyed by ultraviolet radiation or chemical reactions.

The main human activities that contribute to N2O emissions are:

Agricultural soil management such as the use of synthetic and organic fertilisers, manure management, and the burning of agricultural residues.

Fuel combustion based on fuel type and combustion technology, maintenance, and operating practices.

The byproduct of creating certain synthetic materials and chemicals

The treatment of domestic wastewater during nitrification and denitrification of the nitrogen present, usually in the form of urea, ammonia, and proteins.

N2O can stay in the air for up to 114 years. N2O has a GWP 273 times that of CO2 for a 100-year timescale. This means, pound for pound, the comparative impact of N2O is 273 times greater than CO2 over a 100-year period.

Though these values are U.S. specific, they reflect the global dynamic of these GHGs. Following up with sources invested in collecting and estimating this information, such as your nation’s environmental protection agency equivalent, can help you start to understand which activities are within you and your community’s control and which activities involve advocacy and reduction at a larger scale to return these GHG emissions closer to their natural cycles. It gives a point of conversation to collaborate with other stakeholders in an effort to create sustainable health justice.