A Declaration for Health

During the summer of 2024, psychologists, doctors, medical students, and other healthcare professionals from racialised experiences gathered to co-create methods for weaving justice into their practices. This is their Declaration and proposition for a world that rooted in healing rather than harm. As you read, you become part of the Declaration.

About the Programme

This programme drew upon abolitionist principles. We recognise that systems of capitalism, colonialism and other forms of oppression are designed to destroy health and exploit life. They cannot be compatible with health justice. Abolition asks us to dismantle and disrupt those systems, and to simultaneously imagine, build and collectively seed systems of care, regeneration and healing.

This programme is rooted in the idea that health is ecological and collective, meaning that habitat and people are intrinsically entwined. The air that we breathe, water we drink, places we sleep, the autonomy of our communities, all play a crucial role in our health. Therefore, if we want to heal, we also have to be in Kinship with more-than-human animals, our Peoples and Planet.

We are humbly picking up the batton, alongside many others, from the historic and groundbreaking work of The Black Panther Party and Zapatista Movements. Both have established precedent for health justice, specifically in how to create pathways for deep healing through collective care, organising, land-based practices and autonomy.

This programme drew upon abolitionist principles. We recognise that systems of capitalism, colonialism and other forms of oppression are designed to destroy health and exploit life. They cannot be compatible with health justice. Abolition asks us to dismantle and disrupt those systems, and to simultaneously imagine, build and collectively seed systems of care, regeneration and healing.

As scientists and health practitioners this means acknowledging that health is ecological. Meaning that the places we inhabit and our experiences within them affect our health. The contaminated air we breathe is affecting our cellular construction giving way to multiple diseases. The pain and trauma of extraction and contamination that is imposed on the Land, is the same that is being manifested in our bodies through disease.

Therefore, if we are to heal, our practices have to be rooted in Land Justice, Trans Rights, Worker Rights, The Rights of Land and Water Protectors. We also have to be anti-genocide, anti-settler colonialism, anti-occupation, and in concert with abolitionist movements.

Reasons for the Programme

We are experiencing complex and multiple poor health outcomes due to the deliberate and innumerable crises created by extractive economic systems. These crises create more crises as well as amplify current ones.

This programme emerged from two contemplations

We are experiencing complex and multiple poor health outcomes due to the deliberate and innumerable crises created by extractive economic systems. These crises create more crises as well as amplify current ones. For example, Gaza was already experiencing drought and multiple other ecological challenges due to planetary dysregulation and contamination spearheaded by Israeli occupation(source). Now, the Peoples of Gaza have to content with ecocide alongside their genocide, which is creating a transgenerational polycrisis. Simultaneously, the Peoples of Gaza now have to confront these deliberate and multiple crises with an ever debilitating infrastructure, including the death of doctors, engineers, scientists, liberators, and so on. This left us with the following questions;

How does the polycrisis affect human health outcomes?

Do we have the knowledges, tools, and cognitive ability to comprehend the phenomena we are facing? Or do we need to build new knowledge pathways?

Can justice education for healthcare workers help us create health practices that function within the current context?

In the U.K. we are yet to directly face the violence of war, however, we are facing displacement due to planetary dysregulation, increasing mental and physical health crises due to austerity, and the threat of another pandemic. This is being met with an increasingly defunded and thus collapsing healthcare system. The inevitable and deliberate collapse of the National Healthcare Service will disproportionately increase the poor health outcomes of racialised and marginalised peoples, who already experience medical violence, gaslighting and denial of care in the NHS. We therefore need to build new pathways for healing that start at the community level and move upstream to healthcare systems. This contemplation leads to the following questions;

What is the intersection between health justice and healthcare?

How do we practise community primary care and how does it join with healthcare systems?

What tools and knowledges do we need to acquire to mitigate the harm from the collapsing healthcare system?

From the programme co-lead, Rhiannon:

Health has been captured as a tool for the elite and capitalism, through individualism and eugenics, but when reclaimed it is a powerful tool for liberation.

Health workers are isolated from each other and community, encouraged to be apolitical and not allowed to develop the radical analysis which health justice brings.

Our health systems are not serving us, they are violent, individualistic, lacking in many adequate tools, and increasingly privatised, underfunded and surveilled, we need to be able to challenge medical violence from within these systems but also develop new and learn from historical examples of collective healing practices.

Who Participated?

To ensure the programme can facilitate co-learning, we chose participants that worked in a range of spaces. This included Researchers, Sexual Health Advisors, Educators, Doctors, Health Campaigners, Psychologists, Students. Their work collectively spans the intersections of Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights, Racial Justice, Neurodiversity Justice, Gender Justice, Queer Justice and many more.

The Programme Co-Hosts

Rhiannon Mihranian Osborne (she/her) is a junior doctor, organiser and researcher focussed on environmental justice, abolition, anti-colonialism and reimagining health systems. She loves doing grassroots mutual aid work and trying to develop liberatory healing skills. Rhiannon is of Welsh and Armenian-Palestinian heritage and finds lots of joy in connecting through food and music.

Amiteshwar Singh (he/him) is an organiser and student doctor in the UK, with roots within Amritsar, Panjab. To implement his vision for health justice that is rooted within decolonial praxis, he centres his work around the intersections of ecological justice, racial justice and a just economic transition. Through re-imagining health, Amit finds great joy in committing himself to a community-led radical, joyful future.

Araceli Camargo is a neuroscientist and health justice advocate working at Centric Lab. Araceli is a descendant of the original Peoples of Turtle Island.

How we chose participants

Sectors who participated

To ensure the programme can facilitate co-learning, we chose participants that worked in a range of spaces. This included Researchers, Sexual Health Advisors, Educators, Doctors, Health Campaigners, Psychologists, Students. Their work collectively spans the intersections of Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights, Racial Justice, Neurodiversity Justice, Gender Justice, Queer Justice and many more.

Intention to take the knowledge forward: We chose participants who were embedded in different types of community, and had the desire and the seedlings to take the knowledge and relationships forward and spread the seeds we are attempting to sow.

A space for community and shared growth: We chose participants who we felt would benefit from space and time to go deeper into key topics of health justice, and perhaps had not had access to, felt safe in, or been exposed to communal political consciousness raising.

To identify the participants best fit for the programme, we asked 3 core questions:

What does healing mean to you?

What current health justice pathways are you working on? This could include for example activism work community organising clinical work research healing skills.

What learnings from the programme do you envisage applying to future collective liberation and health justice work?

How would you describe yourself?

Practices and Principles

This programme took over a year to emerge from multiple conversations with the Centric ecosystem. We took our time to listen to and observe the world around us, including communities facing health injustices. We took this information and shaped a programme that was founded in Kinship, fairness, safety, and love.

This programme took over a year to emerge from multiple conversations with the Centric ecosystem. We took our time to listen to and observe the world around us, including communities facing health injustices. We took this information and shaped a programme that was founded in Kinship, fairness, safety, and love.

Below is an overview of the methods and principles we employed to shape this programme

Walking: We are ardent, humble and dedicated students of the Zapatista method of “caminar”, which translates directly as “walking”, but it's more than that. It's ambling througha a long journey, where one is listening, questioning, observing the fullness of phenomena. Through this process space/time is created for ideas, thoughts, and concepts to emerge organically and authentically. Additionally, this method allows us to understand that we are in continual motion rather than trying to reach a predetermined destination. This provides the mind with flexibility and calmness, furthering our ability to think.

Gentle Time: “Walking” takes its own time, therefore, we employ gentle time in this and all the work we do at Centric. Gentle time means that deadlines and milestones are reached through listening rather than artificially. We still have to deliver within specific time constraints, but we do not strive to “fit” everything in. This might mean letting go of goals or outcomes that are not for this time.

Kinship: We are Kin to each other, with the participants and their relations, as well as with all other living beings. The Kinship allowed us to work in mutualistic symbiosis where there was no definitive line between teacher and student, we were both, seamlessly and simultaneously. This method created a space where everyone was able to grow, learn, and heal.

Cognitive Arch: We were conscious of creating a narrative arch that made sense to the cognitive learning process. Therefore we started with epistemologies, which was the knowledge origin of the ideas and concepts being introduced, then we moved towards new concepts and ended with contextualising the learnings to healthcare. This arch allowed participants to gently move the minds from one starting point to another.

Skin in the Game: All of the cohort, including the organisers, had what is colloquially known as “skin in the game”. Meaning that we all had deeply personal reasons for participating and creating the programme. We have all been witness to the oppression and marginalisation of our Peoples, which motivates both our roles in healthcare as well as seeking justice education to further our health practices. This common ground was crucial to creating a balanced ecosystem rather than a “teacher/student” report.

Solidarity: Due to the whole cohort having “skin in the game” it was important that we all showed solidarity with their respective histories of injustices and oppression stemming from colonialism, imperialism, extractive economies, and supremacy. This solidarity helped bind the cohort together and create a space where we could all learn and further our justice pathways.

Dignity: All participants were asked to share any accessibility needs they have, to ensure we can provide a tailored co-learning environment. We also provided participants with stipends to facilitate their own healing processes.

NB: we are students of this practice, not teachers or experts. We use this practice within the limitations of our knowledge and implement it within the context of the programme rather than simply appropriating or “cherry picking” what we needed.

Programme Content

Programme content centred around asking and debating the following questions: Who benefits from a purely biomedical/individualistic analysis of health; What are the structures of power and violence (both present and historical) which enable health injustice to occur; What additional factors may explain the increased sensitivity to pollution and worse health outcomes for those in poverty?…and more

Phase 1 - example case and workshop:

In our first session, we explored the concept of allostatic load and ecological health, using the case study of Cancer Alley to demonstrate this in practice. We explored how poverty mediates the relationship between air pollution and health, the environmental racism of oil & gas development sites in the US, and the individualistic responses of public health and oil companies to the health crisis.

Q1: Who benefits from a purely biomedical/individualistic analysis of this situation?

Q2: What are the structures of power and violence (both present and historical) which enable this health injustice to occur?

Q3: What additional factors may explain the increased sensitivity to pollution and worse health outcomes for those in poverty?

Q4: how can an ecological understanding of health support this community in their fight for justice? What alliances could be built using this lens?

Phase 2 - example workshop:

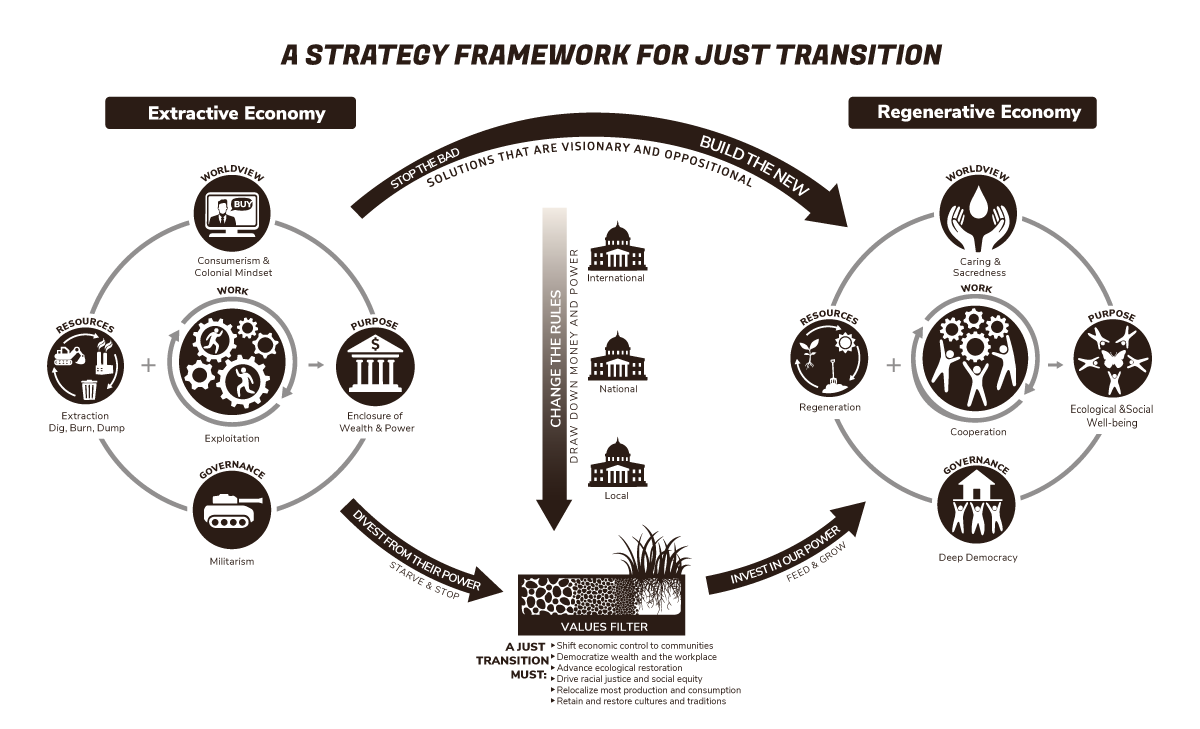

In phase 2, we used the Strategic Framework for A Just Transition, developed by Movement Generation, to explore how ecological health relates to the structures of colonial capitalism.

We asked participants to bring a case study of a health injustice, either from their own research or community, or from the People’s Health Tribunal of Shell and Total, and map the pillars of the extractive economy into this issue.

We then discussed how medical systems are complicit, and mapped how medicine participants in governance by control and militarism, the enclosure of wealth and power, extractivism, the colonial mindset and consumerism.

Methodologies

The design of the programme took shape through discussions with comrades, friends and the study of pedagogical programmes led by groups such as the Black Panthers. The methodologies we employed for the programme varied but included: Purpose to political consciousness; Healing as part of political consciousness; Relationship building; Examining medical violence and revolutionary medicine, and more.

The design of the programme took shape through discussions with comrades, friends and the study of pedagogical programmes led by groups such as the Black Panthers. The methodologies we employed for the programme varied but included:

Purpose to political consciousness:

The cohort of participations we hope to bring into the Centric ecosystem, and the programme was geared towards increasing our shared skills, knowledge and relationships in order to work together towards health and healing justice. Our visions for how we would use this learning, both collectively and as an individual, were discussed, dreamed and embodied in each session. For example, halfway through the programme we develop a collective abolitionist health declaration, committing each other to continued growth and transformation. The participants were encouraged to envision and practise their role in liberation.

Healing as part of political consciousness:

We recognised, both as participants and healers, that we cannot talk about health and healing justice without attempting to connect with our own bodies and minds. Each session included a somatic practice, often taken from the book My Grandmother’s Hands. In the topics we studied, there was immense grief, in particular acknowledging the violence experienced by our siblings in Palestine, Congo and Sudan. We also acknowledged that these topics might be triggered for participants, for example those who may have experienced displacement themselves. We attempted to hold and navigate this grief, and are thankful to the participants for their feedback and guidance as to how to do this. We hosted debrief spaces, and held a joint discussion on what safe and loving spaces look like to participants.

Relationship building:

Time for building relationships between participants was an important part of each session and the programme overall. We set a minimum requirement for participation to support this. Halfway through the programme, who hosted an in-person healing day. This healing day did not deliver ‘content’, but was an open space to explore feelings that were arising as a result of the programme, create a shared declaration, and do a ‘body-territory mapping’ exercise for our movements and communities. The body-mapping exercise was generously taught to one of the facilitators by Dra. Delmy Tania Cruz Hernández.

Application of knowledge:

In advance of each session, participants were asked to absorb learnings from the shared preparatory content, such as through Centric Lab reports. This enabled us to maximise time for discussion, experimentation, analysis and application of learnings. The sessions were spaces to apply the knowledge, through workshops, discussions with the wider community, and really going deeper into how the analysis can be applied. We maximised the time for discussion and experimentation.

A space to understand our own lives and communities:

We did not approach injustice as a concept to be studied external to ourselves, instead participants generously shared their own community, family, and personal experiences with one another. The participants were encouraged to share and apply their own significant knowledge, experience and analysis. To facilitate this, we created a safe and generous space through relationship building, somatic practices and formulating a small cohort size. The political frameworks provided formed a scaffold on which people analysed their own experiences.

Knowledge from the movement:

Whether in our programme resources or our speakers, we centred the knowledge produced and developed by communities facing the brunt of structural violence. We avoided elitist forms of research, and focussed on knowledge that has been situated within struggle. Marginalised and oppressed peoples bear the brunt of injustice, and so are also the creators and curators of knowledges and practices that can achieve health justice. Their lived expertise facilitates accountability and guidance. To truly aid in liberation, health workers must surrender the notion of power ‘over’ and instead build power together in community and solidarity, centring lived experiences of marginalised communities.

Spiral time:

We developed an overarching programme where each phase developed on the previous. However, we recognised that, like the past, present and future overlap and co-exist, political consciousness is not linear. We hosted drop-in sessions during the programme (in the feedback people would have liked more) where people could drop-in to discuss any concepts they were struggling with, emotions that were coming up for them in the programme or how they might want to apply it to their work. We also adjusted the programme content according to the needs of participants.

Examining medical violence and revolutionary medicine:

As the programme was in particular for health workers, the topics and sessions included specific analyses of how health systems in their current form uphold and contribute to structural injustice, create violence and gaslight communities. We created space for participants to talk about medical violence they have witnessed. We explored different models of care rooted in Kinship, resistance and community, such as the Trans community and Indigenous Peoples, and examples of health practitioners engaging in revolutionary work.

Abolition:

Abolition asks us to dismantle and disrupt systems of oppression - we must examine them, understand their interconnectedness, but also move beyond critique. It also demands us to build the community strength and power to overcome them. This requires both care and strategy. The programme topics included how we build care, infrastructures and organising strength to simultaneously imagine, build and collectively seed systems of care, regeneration and healing.

Healing Stipend:

All participants were given a stipend. Instead, it was offered with the intention of being put towards healing. It was up to participants to decide what they needed to catalyse their own healing journeys. Additionally, all in-person activities (and associated travel, food costs etc.) were covered by Centric Lab to minimise barriers to access.

Retrospective

A selection of reflections in the forms of quotes from the programme organisers and participants.

Contemplations from Co-Hosts

Araceli

There were two main moments that stayed with me. The first was the Palestinian doctors who asked the question “what happens when the doctors die?” This created further questions

What happens when key and life sustaining infrastructure is destroyed? How do we reorganise ourselves to meet this phenomena? What do we need to fully be able to understand this phenomenon? What are the knowledges and tools we need to develop to help us move through this era? What are the Ancestral Knowledges that we need to sustain and evolve to meet the health demands of this era to ensure the future of generations to come.

The other contemplation was in the lecture from Zapotec womxn in Chiapas, who have organised themselves to create a health clinic. It provided the opportunity to understand that healthcare can happen in multiple ways and in fact it needs multiple imaginations. This clinic offers an example of what can be done from the bottom up, an opportunity to create pathways of health justice here in the UK.

Amit

A really valuable learning this programme gave me was the experience of being part of a community, albeit small, as it was in the process of being collectively built and nurtured. Together, we explored questions and themes around kinship, dignity, trust and vulnerability through our shared practice.

Another moment that deeply resonated with me was a quote from Abdirahim Hassan, founder of Coffee Afrik, who said, ‘Justice is what love looks like in public’. Coffee Afrik embodies the philosophy of hood futurism to envision the concept of ‘poor and thriving’ through acts of reclamation, such as projects that reclaim ownership of and repaint land in ‘the hood’ as a form of resistance. This led me to question how we can reclaim the right to nourish, and be nourished, by the land upon which we exist.

How can, and is, this concept be applied to other communities, including those beyond the borders of the UK? How can the reclamation of physical land lead us towards reclaiming cultural narratives and histories as well as forming new ones in response to those that have been erased?

Rhiannon

As a facilitator, this programme opened up new avenues of political consciousness and healing for myself. Rather than trying to deliver knowledge, the purpose of the facilitators was to design activities, connections and speakers that supported the growth and nourishment of the participants. This flexibility, openness and relationality allowed me to also learn from them and feel the beauty of seeing frameworks resonate with the participants. I felt seen, loved and supported myself.

The knowledge came alive through relationships, through spaces where people felt solidarity and love and connection, and were able to bring in their own knowledge and connect to it themselves too. Knowledge is only useful in constant dialogue, movement and relationship with people - the knowledge has to be alive by people holding it, and this programme showed me how knowledge can be a form of community power building. What gave people the ability to absorb the knowledge was time and community, as well as the space to apply and feel the concepts and frameworks.

I had almost forgotten how healing it feels, to find people who care as deeply as you do, and to explore the things you care about together, bringing your authentic self to that space. I felt so grateful to be able to collectively create that space together.

It feels so great to be part of building something that feels deep, sustainable and radical. It feels good to build a space that is our own, not campaigning against something or trying to fight within other spaces, but nourishing our own space and power.

Testimonials from Participants

Speaker Highlights

"The Palestine session highlighted how colonisation disrupts relationships of colonised communities and that leads to poor health outcomes, liberation must come in all aspects of life because all aspects of life are impacted and disrupted by colonisation. The intricacies of national identity vs indigenous identity when it comes to healing are highlighted - what is an indigenous healing methodology? How can we archive these practices whilst also keeping them living? The Palestine session also highlighted how much we need healing systems that are able to respond to crisis and emergency, they need to be decentralised, rooted in communities, and not captured by the elite.”

“In the Zapatista feminisms session, we explored how healing practices within the community increased the collective political capacity. These practices had to be rooted in the land, recognising that the river was polluted. People responded to this harm with various autonomous political projects, ranging from domestic violence shelters to ecological restoration to political campaigns, but it all stemmed from a shared understanding of ecological health and a space to heal together.”

Resources and Digital Workbooks

Our favourite references that were shared throughout the programme by everyone involved.

Please see the schedule for the Centric Lab reports and pre-reading which were shared as part of the programme.

Ecological Health

This digital workbook provides definitions and understanding of ecological health. It also has exercises to follow, if you would like to do self-directed learning - GO TO MIRO BOARD.

Epistemologies and Justice

This digital workbook provides definitions and understanding of epistemologies, which is the study of knowledge. This is so important in understanding how supremacy creates its systems, so we can create tools to generate justice pathways and abolition strategies. It also has exercises to follow, if you would like to do self-directed learning. - GO TO MIRO BOARD.

Systems of power workbook

The purpose of this Systems of Power board is to build confidence for community and grassroots led advocacy in health justice issues as they navigate political and governmental systems and their layers of entrenched power.

Right to Pollute

In sacrifice zones, the right of corporations or states to pollute supersedes the rights of the population to health and self-determination. Adapted from the work of Dr Max Liboiron, the "right to pollute" was coined by Centric Lab to describe the legal rights given to industrial polluters to contaminate soil, water and air.

“The state-sanctioned or extralegal production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death.”

- Ruth Wilson-Gilmore on racism

Our favourite references that were shared throughout the programme:

The doctor’s role in liberation: an interview with Dr. Ghassan Abu-Sittah

Hip Hop Architecture: The Post Occupancy Report of Modernism | Mike Ford | TEDxMadison

Terraformed: Young Black Lives in the Inner City - Repeater Books

(PDF) Extractivismo y (re)patriarcalización de los territorios

Bodies, Territories, and Feminisms | Columbia University Press

Inflamed: Deep Medicine and the Anatomy of Injustice by Rupa Marya and Raj Patel

Staci Haines: The Politics of Trauma